High Season Read online

Page 9

My first trip back into town was more fraught than I’d imagined it would be. Considering that I’d left Sydney in a blaze of pain, I wasn’t concerned about things like having a licence to ride the Honda 750 I was on; I wasn’t worried about the out-of-date registration label or the outstanding warrants I had from my Gosford trip gone wrong. I had underestimated what being back in a city meant. Every police car and red light, every bottle shop and happy family, crowded in on me to the point where I got shaky, vulnerable, and I didn’t like it.

My first joint sliced the edge off things nicely. I hooked back up with Angela and caught up with some old friends. I took to hanging out in the local hotel and shooting pool and staying calm. The idea of not using any drugs at all hadn’t occurred to me. I was convinced that my problem was heroin and as long as I stayed away from injecting that, everything else would work out fine. My levels of anxiety convinced me that I couldn’t stay in town permanently, however, and I spent the next few months riding back and forth between the block of land and Brisbane. And I didn’t get lonely for months. It was strange how far a sense of shame or disappointment will keep a person from wanting contact with others. I knew I had blown a great opportunity at the Pasta Man; blown it badly. After a few tastes of Brisbane, though, I was starting to feel the need for company and other people more often. I began to think that what I was looking for out on the property, being alone with nature, was in fact an illusion. It started to feel like what I was doing was running away and what I really needed to do was back myself in the city by getting another job in a kitchen somewhere and making a proper go of things.

17

Sammy has a neat row of coffee cups and petits fours lined up along the bar for Paris and the girls. And as Vinnie bounds up the stairs with his girlfriend Jackie, he looks a little bedraggled, a little like he’s been interrupted from a particularly sweet dream in order to attend an emergency.

Scotty guides Jackie to a table as Vinnie makes a beeline for the kitchen.

‘You guys know what you’re doing?’ Vinnie asks from his command position in the bar.

‘Yes, Chef,’ I reply in a fashion that indicates I don’t want to piss him off any more than he obviously is. Now is not the time to be a smart-arse with Vinnie: that’s just what he’s looking for, someone to unload on for being a wise guy when he should have known better.

‘What the fuck is Paris Hilton doing in my restaurant?’ he asks, shaking his head and lighting a cigarette.

‘No one books any more, Vinnie. It’s a disgrace,’ I say.

‘Fucking kitchen’s a mess, mate. What are you blokes doing?’

‘We’re onto it, Vinnie. We’re going to scrub down now and get ready for dinner. We’re booked out again tonight,’ I tell him.

‘Of course we’re fucking booked out, Jimmy. It’s New Year’s Day, you clown. It’s the only time we ever make any money. It’s costing me a fortune just to keep the doors of this place open.’ Vinnie launches into what’s become a familiar refrain.

‘Scotty,’ Vinnie calls out to the maître d’, who has just returned from seating Jackie and delivering the coffees to Paris’s table. ‘Don’t bother ringing me when my friends turn up, mate. I don’t own the fucking place or anything.’

Scotty has been rehearsing his next lines for a couple of hours now. And Vinnie is aware of that and is keen to disrupt Scotty’s thought patterns in order to gain an early advantage so that he can justify laying the blame where everyone knows it’s going to end up anyway.

‘Don’t tell me my phone was off either, you could’ve called Jackie or GT or anyone else to let me know I had friends dropping in for lunch. I hope you’ve looked after everyone, mate. If I go out there and hear anything other than that I’m a genius and they want to move into my hotel permanently, I’ll fucking sack you, all right?’

‘Yes, Vinnie,’ Scotty replies, not stopping long enough to listen to anything else the boss has to say. And really, Scotty has heard it all before, but that doesn’t lessen an onlooker’s joy in watching the kill.

‘I might just sack you anyway,’ Vinnie calls after him. Then he turns abruptly. ‘Don’t you fucking laugh, Jesse. What were the police doing in my hotel this morning? Yeah, I heard all about it, mate. You think I don’t know everything that goes on in my hotel? And you—if I catch you smoking weed one more time you’re gone, all right?’ Vinnie tells Choc. And he’s serious: seriously pissed off and completely sober. Which is rare and a little more real than anyone is used to.

And it’s not that Vinnie isn’t a good bloke when he’s not drinking, it’s just that he’s been caught off guard by Paris and her crew coming for lunch and not phoning ahead. He’s unsure how to play this one out. Part of him is angry that the dickhead who brought her here didn’t let him know they were coming, and another part of him is wanting to be the gracious host anyway and lay on a few drinks and treat them all like the rock stars they want to be. But the fact they didn’t call him . . . you can feel it winning the battle between good host/hurt friend.

‘Are you and Jackie joining Paris for lunch, Vinnie?’ I ask him, trying to break the tension.

‘Fuck them, mate. They’ve already eaten. Give me a small steak and chips with mustard—and I mean small, all right? Don’t send me out half a cow again or I’ll sack you too.’

‘Yes, Chef,’ I reply. ‘Jackie having the fish?’

‘Yeah, give her the fucking fish,’ Vinnie sighs. ‘And not too big, she’s getting fat.’

‘Yes, Chef,’ I say, nodding, careful not to laugh. There’s a time to joke with Vinnie and a time to do what you’re told and say as little as possible. Some people don’t understand that and they tend not to stay long at Rae’s. Vinnie doesn’t want the truth, or anything that smells remotely like it: he wants what he wants and if you can’t figure out what that is—well then, you’re a silly cunt who doesn’t know anything.

‘Fucking Scotty,’ Vinnie says, shaking his head as he stubs out his cigarette and walks off into the restaurant to take a seat at his table with Jackie.

The thing about Rae’s on Watego’s is that it’s not like a lot of other fine-dining restaurants or large hotels. It’s a really small and intimate space that Vinnie owns and runs like his personal mansion for a select group of friends. If you stay at Rae’s, you’re a friend of Vinnie’s. And if you’re not rich and famous before you arrive, you’re going to feel that way from the moment you pull into the drive.

‘You still going into town, Jesse?’ I ask.

‘I’ve got to, Chef. I won’t be long,’ Jesse answers. And now I know that whatever’s going on for the boys is fairly serious. Jesse wouldn’t risk a shouting match with Vinnie if the stakes weren’t high.

‘It’s no biggie, Chef. I’ve just got to see someone about a room in their house.’

‘Are you moving?’ I ask.

‘Yeah, I’ve got to,’ Jesse replies.

‘Get Vinnie’s salad started, okay?’ I tell him.

‘Yes, Chef.’

‘Not a good time to be moving, Jesse.’ I state the obvious, again.

And Jesse and Soda laugh dismissively, like, no kidding, Einstein.

‘Soda, get back on the dishes, mate. Jesse can finish up his section now.’

‘Yes, Chef,’ says Soda, who takes it like a man and heads back down to the steaming end of things.

‘Let me know if you get stuck, Jesse, all right?’ I insist.

At which Jesse turns around and nods. ‘Thanks, Chef.’

‘I mean it. I know you don’t really want to move in with Alice and the boys, but there are alternatives to having nowhere to live.’

‘Yes, Chef,’ Jesse replies. And I know he wants me to just shut up and let him handle this. And I would—normally—but physically, I cannot do both his section and mine. If I have to do both sections because he loses the plot over moving house or anything else, it will break me. That’s what I know. And I might not know very much else about anything much, but I know that ha

ving to do Jesse’s section as well as mine will send me into a space where I might shatter into very tiny pieces. And no one wants that. This is a party house in a party town. All anyone wants is to have a good time; blow off some cobwebs and a few of last year’s disappointments and loves gone wrong. It’s not a crime to want to suck back some pleasure at this time of year. The hell of Christmas with family and weirdo relatives has been and gone; all the broken dreams of last year have magically disappeared via the countdown last night and now . . . it’s a new dawn. And on this brand-new day, this fresh and forgiving New Year’s Day, people are entitled not to be stuffed around by some dickheads in the kitchen who couldn’t organise a picnic basket. Really, I understand that. I had the high season off once too. It’s just that there are limits to what a man can do. And given that Jesse has let the line down before by not turning up, I feel compelled to ensure it doesn’t happen again.

Last time Jesse didn’t turn up for work it was understandable: his girlfriend had got drunk and taken up with someone else while they were all out at a nightclub. I could feel his pain, but it was me that had to pick up the pieces and do his section as well as mine. I got away with it then because it was winter. Rae’s is not busy in winter; some days we do no one at all in the restaurant. You spend all day prepping up your section’s mise en place and then, during service, kill an hour or two staring out to sea with Scotty in the restaurant. We still have to bake the bread rolls for lunch; we still have to pound the nahm jim in the mortar and pestle for the freshly shucked oysters At the end of service, we either have a staff lunch or throw the lot out and prepare everything again for dinner. The small quantities we prepare reflect the reality of not having any bookings—and, of course, we are obliged to keep the food costs to a minimum. The cold months in Byron Bay can be a wasteland in the hospitality industry.

But that’s not the quality of problem we have today. From Christmas Day through till the end of January we are booked out. Every room, every lunch and dinner service, the place is bursting with people looking to have the time of their lives. It’s a blast—for them. Generally speaking, everyone knows what they’re in for at Rae’s because they’ve been before, and most of them will stick their heads into the kitchen and say ‘Hi’ or ‘Thanks’ or, if they’re on a first-name basis with the chefs, ‘You’re a disgrace, Jimmy. That was terrible,’ and then run off, giggling, to the bathrooms. It’s a real gas.

‘Why do you have to move now, Jesse?’ I ask, frustrated. And I know I shouldn’t say anything, I know everything will probably work out fine, but I can’t let it go.

‘Fuck, Chef!’ Jesse shouts, and storms out of the kitchen. ‘I’m going for a cigarette.’

‘Two minutes!’ I call after him. And that’s being generous. You can’t have your line cooks telling you how things are going to go. That just doesn’t work. It never worked that way when I was down the line and it’s not going to work like that at Rae’s—not today or any time soon.

‘He could stay at my girlfriend’s place, Chef, if he gets stuck,’ Choc suggests in his good-natured way. And when he says it, I can see Soda down at the dirty end of things smile and shake his head like, which boat did you just get off?

‘That’s very nice of you, Choc. Too bloody nice, mate. But I wouldn’t let Jesse anywhere near your girlfriend when you’re not around.’

And Choc laughs. He’s a Kiwi, he’s young and generous, and where he comes from everyone’s family.

‘He wouldn’t want to drive out to Dunoon anyway, I guess.’

‘No, mate, he probably wouldn’t,’ I say.

What Choc doesn’t quite get is that, while it’s imperative Jesse turns up to work and takes his place on the line, he’s nothing more than a bundle of frazzled nerves and overtired muscles. Working long hours in such a small, hot, cramped space, surrounded by other men, has made him desperate for anything that might remotely function as a form of relief. And you don’t leave people like that unattended around your loved ones. It’s not fair. What you do is keep them on a very short leash and you tug it every now and then in order to keep their mind on the job.

I open the oven and squeeze Vinnie’s steak between my forefinger and thumb to check where it’s at: another three minutes. I season Jackie’s piece of fish and press it into a very hot pan, skin side down. It’s a small piece of fish, just like Vinnie asked for. It’s smaller than Jackie will want but its size will give Vinnie some perverse satisfaction, particularly if she complains, which will open the door for Vinnie to start nagging her about her weight. That Jackie is slender, fit and trim is not the point. The point is, Vinnie is pissed off, aggravated and skinny and he prefers everyone around him to be pissed off, aggravated and skinny.

Out through the pass I can see that Vinnie has positioned his chair so that his back is towards Paris and her friends. This sets him apart from the other diners in the restaurant, all of whom have their chairs casually aligned so that they are able to both eat their meals and converse with their lunch companions while simultaneously staring at Paris Hilton. I don’t know what it is about some famous people that manage to pull focus in such a magnetic way. Most people will cop a look at someone famous if they’re in the same vicinity, but Paris seems to have become something more than that; she’s a weird cultural fascinator constantly caught in the light of other people’s gaze.

When media commentators talk about Paris Hilton as if she’s some sort of strange, nothing celebrity, famous for being famous, I would argue they miss the point. Last time I checked she’s famous for being a brain-bogglingly rich heir to a hotel fortune. And she’s been in the spotlight for that reason (as well as the fact she’s okay to look at) since anyone can remember. And cooking lunch for her while she’s in a hotel restaurant seems somehow right. I’ve got no doubt she never stays at any Hilton hotel, or if she does it’s in a room I don’t know about, because she’s far too classy for that brand. She’s a fucking ambassador for God’s sake, for her and her family’s fortune. Having Paris constantly in the media, commented on and commenting on various topics, is like having a blank cheque to market your hotel chain. No one else might have noticed, but I seem to recall that the Hilton hotel chain has refurbished just about every high-rise building they own in the last few years. They have probably done that because they can afford to, and the reason they can afford to is quite possibly because Paris has made what was fast becoming a crusty seventies brand sexy all over again.

Part of Paris’s image problem is no doubt tied up with perceptions of what constitutes hospitality. For some—and their numbers thin out as you get into the five-star end of things—hospitality is simply a service industry that caters to the most functional aspects of travelling: a bed to sleep in and a room to call one’s own for a night, while the serious business happens during the daylight hours, away from the hotel itself. The hospitality industry is a sort of necessary evil for those travellers in the sense that you have to take your body with you. But that’s not how it is for people with either substantial amounts of money or a keen appreciation for the finer things in life. For this select group of individuals, hospitality makes up their most treasured memories and they love nothing more than to capture an audience with stories about their favourite chalet in Norway or their top-secret guesthouse on the south-west tip of France where Alain, the owner/chef, prepares the most exquisite little pastries for morning tea. And the wine at Chablis! Really, for those people, hospitality is like the meaning of life; it’s what gets them out of their king-size beds each morning. And the secret of their passion lies in how they have inverted the rubric of hospitality whereby the discovery, appreciation and conversation about the various and complex ways in which hospitality might be delivered and enjoyed becomes the reason to travel, rather than a necessary extravagance of any particular journey.

Given that everyone needs to eat at least a couple of times a day and to sleep at some point, the how, what, when and where of those universal needs describes what hospitality does. For

some people, meeting those needs is an art form. It’s what they most like doing. As a chef, I don’t often get to know what these people do or how they come by their money, but since everyone has a choice about how they spend their own dollars and cents, the people for whom hospitality is not so much a luxury as a goal are my kind of people. They are not so much critics as connoisseurs, carefully weighing up various elements of a particular dish or glass of wine or the quality of a hotel’s sheets. And they are not just looking for what is familiar; if that was their goal they’d return to what pleases them most and never stay in new places. But that’s not what they want; they are looking for new and ever different ways to experience hospitality. And given that notions of what constitutes the new will never end, the search for the next extraordinary hospitality experience becomes the reason for the journey.

The perception that the hospitality industry is a sort of large, indestructible, slow-to-change business model that functions the same way across the globe is deeply flawed. The reality is that most restaurants don’t last more than a couple of years and that if hotels don’t constantly reinvent themselves, they go out of business. What never changes about the hospitality industry is the need for hospitality; what functions as an aspect of that industry is constantly evolving. Just as chefs job-hop from one restaurant to the next, so do hotels open and close. Empty spaces that are set up to provide hospitality are constantly bought and sold, their stainless-steel skeletons inspiring an endless chain of spaces that, when they are brought back to life, describe what the hospitality industry is at any given time.

‘Vinnie wants a bowl of chips with his steak,’ Scotty barks into the kitchen.

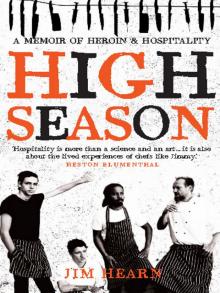

High Season

High Season