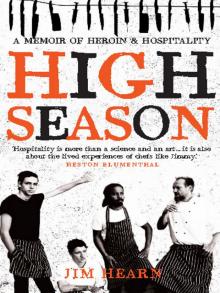

High Season Read online

Page 4

The sensation of my heart pumping heroin through my bloodstream was profound. Prior to that moment, life as I understood it could be depicted as a series of random sketches that formed a clumsy whole. Now it had all come together in the most warmly felt of ways, like hollandaise sauce. The sunlight was not simply light, but a matter of hues, shades and heat. My limbs, with their niggling pains and clumsiness, became coordinated. My mind was aware but not critical; accepting, peaceful . . . relaxed. And after the pinging rush, there was no confusion or anxiety; no physical pain or nagging voice in my head drawing my attention to ridiculous details. And it was perhaps this quieting of my racing mind that brought me the most relief. It hit me that it was okay to let go occasionally, all right to kick back and let things slide. Until that shot of smack, life had been a survival course, full of unexpected plot points, hair-raising bends and curves, unforeseen sniper attacks. It was wearying. I was ready for a little I don’t give a fuck time. And as I lolled back onto a milk crate and stared in wonder at the magic of a slowly revolving ceiling fan, I reasoned that if being loved could ever feel half as good as this, then I had never been loved.

On one level, the next eight or nine years were pretty repetitive. And while it’s true that nothing’s as sweet as the first time, not all of it was bad either. There are plenty of junkies who have used more dope than I’ve spilt; it’s just that everyone’s different about these things. What I had no problems with was the culture of being an addict. I seemed to slide on in there like I was born to the role. And maybe I was.

During my time at the Bondi, other than learning how to use heroin and various other cocktails of drink and drugs, I also learnt how to cook a steak. And let’s be clear about this: steak here is beef. It’s not pork or lamb or chicken or duck or fish. Steak comes from cows and the best beef for eating is Angus. And I’m not into discussing this with any real openness to other ways of knowing beef; far too many chefs and backyard barbeque cooks think they know a lot about beef and, to put it bluntly, they don’t. Cooking beef is one of the most underrated skills a chef might acquire. How hard can it be? Let me tell you, cooking steaks, particularly the thick eye fillet or tenderloin, how the customer orders it is quite an art. And the reason for this is that every steak is different. There is no such thing as a perfectly timed steak and I know plenty of restaurants that buy portion-controlled tender cuts to try to get around the difficulty of inconsistent portions of meat, but they aren’t worth the premium.

Cooking steak is a feel thing; you’ve got to develop a sense of touch around the flesh of animals that becomes finetuned, accustomed to degrees of cooking. A good chef ‘knows’ when a fillet steak is medium well or medium rare or just on medium and they ‘know’ because they develop a sense of touch. By squeezing a steak while it cooks, a chef can develop an appreciation of what stage of cooking the meat is at. There’s no quick and easy way to get to the point of consistently ‘knowing’, you just have to develop the skill.

One of the best ways to teach a chef how to cook a steak is to put it on the menu as a sliced dish. For instance the dish might read, Sliced Angus tenderloin with yam puree and shitake mushroom jus. Now the reason the tenderloin is sliced is because the chef, which in this case is me, is training an apprentice to cook steak. I want Jesse, Choc or Soda, or whoever it is in the next joint, to gain confidence in their ability to cook steaks by seeing and analysing the inside of every steak they prepare. So after they’ve seasoned the lump of beef with salt flakes and white pepper, and seared all the surfaces of the steak in their cast-iron pan, the fillet goes onto a clean tray and into the oven. Here’s the other thing: every oven is different. Doesn’t matter if Chef Pete puts it in for two minutes and Chef Jane says three and a half and Sous-Chef Donny goes six . . . Every steak and every oven is different, and the only way to get a steak medium rare, as the customer ordered it, is to be able to pinch the steak between your thumb and forefinger and know it’s got a while longer in the oven or it’s done. And done means it’s ready to be rested. The steak needs to be transferred to your protein tray in a place where it is going to stop, or very quickly slow, cooking. It needs to be rested so that the blood can congeal or drain from the piece of meat before it gets plated up.

But before I let the apprentice slice the fillet, generally into three thick slices at a nice angle, we look at the steak, we touch the steak, we talk about the steak and watch as the blood soaks into the tea towel which sits on the protein tray. We slice the fillet and all agree that this is a perfectly cooked medium-rare fillet of beef and we discuss what it felt like when it came out of the oven—whose breast or bicep or thumb it most reminds them of. We do this because it’s important to try to remember that touch. The steak is hot when it comes out of the oven and it always looks more cooked than it is because we’ve seared it until the flesh has caramelised but the touch . . . cooking steak to order is all about the touch.

After I’d been at the Bondi Hotel for some time, it occurred to me that my twenty-first birthday was fast approaching. It also struck me that despite the irrefutability of time passing, I felt for the most part that I was in some kind of holding pattern. Don’t get me wrong, I was happy there; it was a warm and cosy space. I was also in some kind of prime-of-life, object-of-desire phase, and the girls I was hanging out with didn’t mind me stoned; in fact, they seemed to like it.

I was sharing a flat up the road from the hotel in Bennett Street. It was a nice top-floor apartment that some boys from Canberra had rented and they were happy for me to pay an equal share of the expenses and crash in the sunroom. The view was all apartment building rooftops and Bondi skyline. None of the boys in the flat were attached to partners in any serious way, and other than Paul, our resident gay nurse, we all worked at the hotel. Sean had the bottle shop five days a week, Damian pulled beers in the rooftop beer garden and Bruce . . . I don’t know what Bruce did, he just turned up for work. Basically we lived like kings. And despite the boys getting a little worried about my drug use after a year or so, my twenty-first acted as a catalyst for us all to pool our collective resources and organise a blast.

We decked the flat out in trippy fluorescent-tape wall patterns and ultra-long-bongs. The bathtub was overflowing with the best the bottle shop had to offer and we scored a veritable smorgasbord of drugs through our friends at the hotel—all of whom decided they weren’t going to miss out on the action and turned up on the night. The flat was so crowded at one point that people literally couldn’t move. Such was the interest in the party that I bumped into several undercover cops, a large variety of junkies from various surrounding suburbs and three different girlfriends from two different states. The Saints, the Smiths, the Velvet Underground, New Order’s first album, Yello, the Pixies, Alien Sex Fiend, Johnny Cash and the Pogues . . . all were there in spirit if not in person, and I got so blissfully stoned with so many different people that—despite not really being able to focus on how Angela could actually be here from Brisbane while Marie from Paddington was wrapped under my right arm and Gayle from the hotel was giving me grief every time she caught sight of me—the night was a raging, police shut-down, music-ripping success. Except for some random bacteria that found its way into a syringe and blew up my groin in a way that was very far from normal. I didn’t notice it until the morning after, and thankfully Paul had the good sense to get me to hospital, where I spent the next four days in a ward being lectured on how close I’d come to forsaking my capacity to father children.

Ward 4D was a window through which reality threatened to shine too brightly upon my youthful, hazy, drug-addicted ways. I did wake up to some things: I realised that, despite lying to the admissions doctors, I had become a self-injecting, poly-drug user; and I was drinking an amount of alcohol which sounded like a wild exaggeration when I admitted it to others. Yet I wasn’t ready to consider giving up or cutting down on any of it. I’m sure I promised everyone that I would but, really, most of my so-called problems seemed like very distant concerns.

>

When I did get back to work, I started to pick up some shifts as a glassie after my shifts in the kitchen. Money was tight; I was young and the extra hours picking up empty schooner glasses off punters’ tables didn’t bother me. I figured I was going to be hanging around the place after work anyway, playing pool, smoking joints and drinking, I might as well be earning while I did so. Then I scored a solo shift in the drive-through and the thing about that was—and you have to remember this was pre-CCTV and pre-mobile phones, pre-internet and EFTPOS—being surrounded by an endless supply of bottles and cases of alcohol and cartons of cigarettes and a cash register which I was responsible for . . . well, it brought about a short sojourn out of the kitchen and into the world of being a drive-through attendant.

7

To be fair to Jesse, his parking run-in with the police was not completely unexpected. Parking at Watego’s Beach during summer is a nightmare. And the particular skill set that finding a park entails deserves special mention. I know lots of places get busy over summer or winter or whatever the particular high season of that place is, but Watego’s—a tiny suburb tucked in beneath the lighthouse on the most easterly point of Australia—is another thing altogether. We’re on the very tip of things and while the vast majority of cars don’t veer left off the road that leads up to the lighthouse in order to roll down into Watego’s, those with the money or the longboards or the parking skills do, and enter what is a very particular kind of paradise.

Watego’s is made up of about a hundred houses. All of them cost at least a few million dollars and some of them considerably more. It’s not an ostentatious suburb to look at; in fact you hardly notice the houses for the blue-green sea, the dolphins, casuarinas and pandanus trees. The local council has graciously installed a couple of free barbeques beneath timber huts right on the beachfront and these are a great option for people—in winter. Winter is a great time to visit Watego’s and Byron Bay generally. You can move around easily, park anywhere you want and fire up as many free barbeques as you like. Have all three barbeques for yourself if you like.

But I guess that’s like going to the Snowy Mountains in summer—it’s strictly for the bushwalkers. And I know bushwalkers are people too, but they usually prefer pushbikes to cars and strange amalgams of hydrated vegetable matter over a restaurant meal.

I swung left off Lighthouse Road this morning on my way to work and attempted to roll down the hill to Rae’s; it was a fucking traffic snarl at nine o’clock in the morning! ‘Don’t you people have anything better to do?’ I was yelling out my window. And of course they don’t. They’re all on holidays and are all determined to mark out their patch of sand on Watego’s Beach. There will have been ‘sitters’ assigned to the barbeques by seven in the morning; no doubt for a child’s birthday party or a fiftieth wedding anniversary or some random backpacker gathering.

As I crawled down the hill to Marine Parade I was greeted by about thirty vehicles backed up waiting for a park close to the beach. Anyone who walks up from the beach, even if they’re only going for a shower, has sixty pairs of greedy eyes on them, tracking their every move.

To add pressure to proceedings, my wife Alice texted me a second picture of our two young boys fighting with each other. There was no message to accompany the image; she was relying on my ability to join the dots. After fifteen years together we can read each other’s shorthand. This picture was designed to remind me that if I didn’t work a million hours a week I would be home on New Year’s Day helping her with the kids; at least to the extent that they would be hitting me rather than each other. Alice knows she can turn my car around with one softly spoken word; turn it around and have it never head back this way again. But right now, in the middle of this particular high season, we’re both content to keep taking cheap shots at each other to alleviate the stress. There’s a point where it isn’t fun any more and people can get hurt, but for the moment we’re just letting off a little steam.

Alice is disappointed that I’m not at home with the family today. Part of the deal with getting Christmas Day off was that I agreed to work every other day over the summer break—including New Year’s Day. Really, she’s seen it all before in regards to chefs and peak seasons and anyway, the photo of the kids fighting is just to remind me what it’s like for her, having to deal with the boys by herself all summer. She needs to know that someone else can feel her pain.

Our eldest son is a full two years from going through puberty, but he’s practising. It’s a compelling performance. And it’s a show that’s been going on for about six months. As a team, we’ve recently surrendered to the idea that our children now have a speaking part in the small drama that constitutes our shared lives. Suddenly our kids are people too. None of the lines our boys are trialling are original nor are they anything we haven’t heard before—it’s just that we’d been suffering the delusion that only other parents had nightmare children.

Alice also understands completely that in order to meet the weekly demands of a modest mortgage, school fees and the running costs of two very second-hand cars, one of us has to work sixty to eighty hours a week somewhere, or we have to split the money-earning responsibilities and work around each other, juggling the kids as we go. We’ve tried both methods of family management and arrived at the conclusion that being young and irresponsible is grossly underrated.

Alice was twenty years old when we met. I was twenty-eight and sitting in a modest room above a suburban church. She walked in with a friend and within the first hour I knew I was studying my future bride. She was the opposite of me in nearly every way but I recognised her every look and mood. I knew why she glanced away or pulled at her hair or wriggled in her seat or coughed. I knew that the reason she glared intently at the boy sitting next to me was to deflect my love-struck grin.

From that first night it seemed clear to me that she possessed a particular kind of vulnerability that I was born to care for. There was—and is—something fierce and innocent about Alice. Normally I would have been more modest in my aspirations but there was this split second when she did return my stare and . . . that was all the time I needed. I was reborn, remade, recast and she quickly became the reason I breathed, woke up, caught the bus and went to work. In the story of my life, Alice has all the winning lines. As soon as I’d pictured us together, I became convinced that nothing bad could happen. And in the strangest of ways, I was right.

Not that she would have anything to do with me for the longest time. To suggest I was obsessive in those early days is an understatement. I was a badgering, hounding lunatic. And it wasn’t until I convinced her to come out with me to a few decent restaurants that she glimpsed some faint potential. At an assortment of cafes, restaurants and wok-shops, I found the confidence to talk and act in a way that didn’t mark me out as just a lunatic. I was a lunatic who could cook. And as the number of restaurants that we sampled grew, she began to allow me into other parts of her life. Sometimes she would let me pick her up from college. One red-letter day she took the risk of introducing me to some of her student friends, who I worked so hard at trying to charm that she desisted from any further such introductions for a long time. And yet I remained irrepressible: eager to lock things down, tie things up and throw away the key.

‘I’m not ready to settle down,’ she’d say. ‘We’re so young!’

It was a logic that was obvious to everyone but me. I was, apparently, tone deaf to the finer points of romance. But my life hadn’t really unfolded in such a way that I could imagine how two people might go out on a few dates and have a little fun while they got to know each other. I seemed destined to always be the obsessive-compulsive smack-before-breakfast kind of guy who thought getting to know someone was the risk you took if you happened to wake up later than expected. (‘Sorry . . . what was your name again?’) And that wasn’t the sort of thing Alice was up for.

Basically, I didn’t know what fun looked like if it didn’t come in the form of white powder—or beige or pink or brown

or tar-coloured or . . . any colour of the rainbow.

Of course Alice has never forgiven me for winning out in the end. Our saving grace is that we did manage to spend five years together before the first of our two boys arrived. In retrospect we could have enjoyed a couple more. But what are you going to do?

As the third picture comes through on my phone I can sense that an actual call is not far off. She’ll start by asking something like, ‘Did you get the pictures?’ And then follow up with some breaking news about not having any idea what to do with the kids day after day . . . without any money! And some time later, when the rest of the world’s asleep, we’ll wonder aloud how it all came to this and convince ourselves once more that, just like every other year, this high season will end too.

But this morning, like every other morning of high season, my most immediate concern was parking.

Off to the left, at Rae’s, there’s parking for about five of the guests’ cars after Vinnie has lodged his Porsche sideways across the driveway. And while to roar down Marine Parade and screech up the paved drive at Rae’s—which is the last strip of privately held real estate before the beach—is not everyone’s idea of being a made man, for some it’s a particularly sweet fantasy.

As luck would have it this morning, my secret parking spot was not taken. It’s a spot famous among the staff at Rae’s, right outside Deke’s house, which, if he’s not entertaining, he doesn’t mind you using. It’s a real treat. And it’s morally uplifting to be able to park there this morning. And it’s not that I hate tourists—tourists are my bread and butter; I’m nothing without their desire to wine and dine at Rae’s—it’s just that because everyone else in the neighbourhood is on holidays there is often a certain tension between the stressed-out, overly tired, heap-of-shit-car-driving chefs and the rest of the punters. Quite simply, they don’t get it. And that’s okay! I’m sure I’d be a fish out of water in their world.

High Season

High Season